Is Nonviolent Policing Possible in Brazil?

From the Series: Protesting Democracy in Brazil

From the Series: Protesting Democracy in Brazil

I had followed news coverage of the protests in São Paulo, Rio de Janeiro and Brasília since June 6, but it was not until personally taking part in one of them that I understood what people mean when they talk about police violence in Brazil.

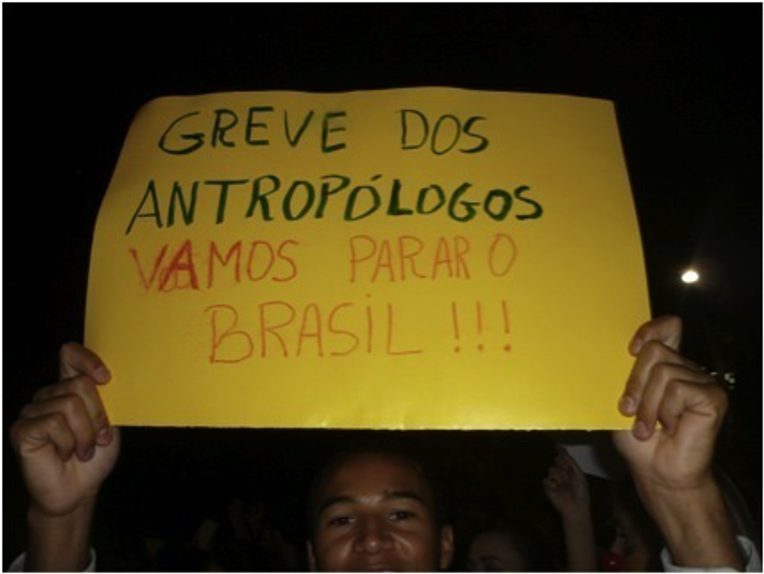

On June 20, I joined colleagues and students from Campinas State University in the protests that were taking place in this medium-sized Brazilian city (approximately 1.5 million people). I shared in the peaceful movement of the demonstrators, and watched as a plethora of demands surfaced—from better healthcare and public schools to fewer legislators. Sayings such as “FIFA pay your fare" resounded in our ears, combining a discontent with the large sums recently spent on World Cup preparations with upset over the rising costs of transportation. But the one thing that everybody chanted clearly in unison—and which became the motto of the night—much as it had in the protests in São Paulo, was Sem violência (“without violence”).

It is estimated that we were among five thousand demonstrators. We were moving along the city’s main streets. When we began moving towards the protest’s point of culmination, City Hall, several streets were completely blocked by well-equipped police, including both the military and municipal police. Furthermore, throughout the parade, the police would occasionally throw stun grenades that sent a chill up your spine, like the first thunder you hear from an approaching storm. But this ostentatious interference with the demonstrations made something clear to me: it was the police that were provoking the confrontation. It was violence-as-containment. In this way, they created a scenario of repressive—not negotiated—control, as they used to, as sociologist Machado da Silva put it recently.

Paradoxically, according to Silva, the demonstrations have been peaceful. Indeed, considering the precarious and heavily individualist organization of some daring "troublemakers" and "vandals" (as they were dubbed in the press), if the demonstrations had not been fundamentally peaceful, Brazilian cities would have been thrown into utter chaos. Campinas was not the city that saw the greatest police violence. But this did not mean that Campinas was exempt; police violence did occur here, with its damage and arrests. Later, when we watched what was happening in other places, the consonance and agreement between the forces of order became clear.

My experience was that when the police interrupted the route so that we could not reach symbolically important locations of political decision-making, the chant “Without Violence” didn’t not lose its poetry. But it didn’t move me the way it did before the interruption. The pact seemed to have broken. The police demonstrations made it so that demonstrators either needed to accept what felt like a dare, or else fall back. The greater meaning of the demonstration becomes lost, replaced by violence and dispersion, a paralysis of both the act on stage and history itself. And in this way, we caught a glimpse of what can be called “anti-politics.” Prevention as a strategy and tactic eclipsed. Police decided they were going to be violent and a few protestors decided that they should answer the police invitation to violence. Several demonstrated they were tired of police brute force, at times even lethal force, like what happened later in protests in poor communities in the Maré neighborhood of Rio de Janeiro.

These sorts of moments reveal the modus operandi of the police, and suggest that it is built on territorial control and violent force. At these moments, the relationship between the police and citizens inevitably becomes frayed. Our dictatorial past is carried into the present, and remolded.

Even in a world in pieces, police in a democracy are meant to protect and create security, not invade; the force is meant to work intelligently in crowds, not treat people as "the masses." In other words, police action should really maintain public order, not lead to public disorder.

Among other issues, the police and their militarism are part of this collective revolt that has taken Brazilian cities. For years now, anthropologist Luís Eduardo Soares has been raising the alarm about this. But according to Silva, what the middle class, the most represented class in the demonstrations, yearns for is to maintain police protection for the freedom to come and go in cities.

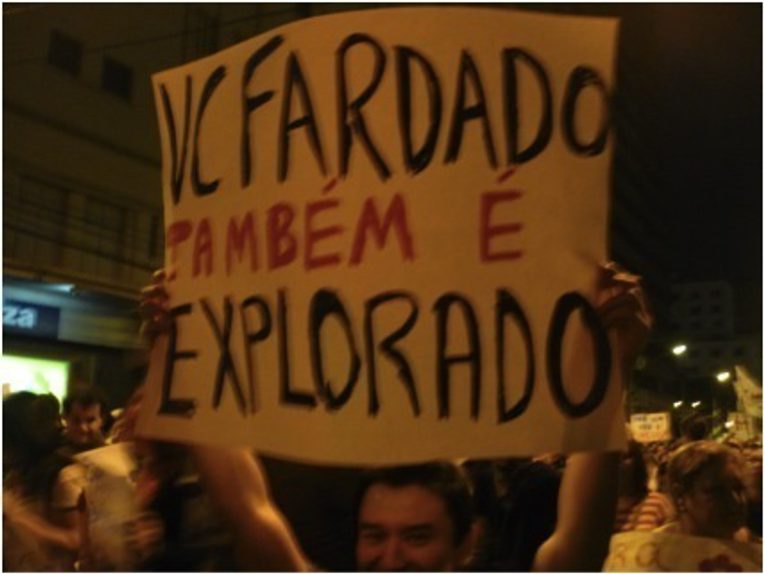

The protests have been an exercise in a more plural and visible form of political intent and staging. As Adorno said in a gathering of social scientists at the University of São Paulo, the protests are shot through with subjectivities; they are the experience of interrupted political communication. In this context, an anonymous letter from a Military Police Officer entered the picture and circulated through social networks, revealing his "internal conflicts, moral earthquakes, ethical hurricanes” when policing demonstrators in São Paulo. One of the signs in Campinas read: “Uniform wearer, you’re exploited too.”

But the widely contested reprise of police violence brought new data with it. As Adorno argued, the discourse connecting politics and police violence is being re-calibrated. For many, violence is no longer considered a legitimate means of politics. Have we not achieved the conditions to demand violence-free politics?

However, President Rousseff, in her state-of-the-union address a day after demonstrations in Campinas and other cities, did not once refer to the police and their excessive use of force. Every time one shies away from a politically-explicit evaluation of policing, the cards of power are mixed up (violent police governs) even if the military police are under the power of states and not the federation. To give one example, scandalous images of extremely violent police operations in Joinville Regional Prison have recently been published. If you, dear reader, take the trouble to watch the footage you will be forced to ask: how far can the police go? As such, one other question the protests oblige us to ask is: In the future, will it be possible for Brazil to have a democratic police?