Nesting Paternalisms: Postwar Indo-Lankan Diplomacies on Sri Lanka’s Plantations

From the Series: Majoritarian Politics in South Asia

From the Series: Majoritarian Politics in South Asia

May 12, 2017, was Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s second official visit to Sri Lanka, but the first any Indian premier would make to the island’s Hill Country after Sri Lanka’s independence. The Hill Country is home to one million Indian-Origin Hill Country Tamils living on the island’s tea plantations. Arriving from India, this formerly migrant, ethnolinguistic minority has been sidelined by Sinhala Buddhist and Tamil nationalisms and postcolonial consolidations of caste and class oppression for over two centuries. This political exclusion intensified with the civil war (1983–2009), effectively stripping multiple generations of their civic and economic rights.

Unlike past Indo-Lankan war-related entanglements,1 the trip aligned well with Hill Country Tamil politicians’ patronage of ruling Sinhala Buddhist parties and presented a high-profile opportunity for them to secure social and financial capital postwar. Both countries’ mutual displays of majoritarian diplomacy manifest in a sensorium of plantation paternalisms. Dissipating the historical specificities of long-term struggles, this sensorium nests in Hill Country Tamils’ ordinary desires for wider political recognition and fulfillment of their basic needs.

On May 12, Modi addressed a crowd of thirty thousand Hill Country Tamils on Norwood Grounds. In front of Sri Lanka’s former president, prime minister, and Hill Country Tamil parliamentarians, he remarked:

You and I have something in common . . . Chai pe Charcha, or discussions over tea, is not just a slogan. Rather, a mark of deep respect for the dignity and integrity of honest labour . . . We will never forget leaders like Saumiyamurthy Thondaman, who worked hard for your rights, for your upliftment and economic prosperity. Kaniyan Pungunranar, a Tamil scholar had declared more than two millennia ago, Yaathum Oore; Yavarum Kelir, meaning “Every town is hometown and all people are our kin” . . . You have made Sri Lanka your home . . . You are the children of Tamil Thai.

From 1939 until his 1999 death, S. Thondaman, co-founder of the Ceylon Workers’ Congress (CWC), led Hill Country Tamils’ fight for citizenship and equal rights. In 1999, his grandson, Arumugam Thondaman, assumed CWC leadership until his unexpected death in May 2020. The family’s patrilineal legacy nests deep within the material infrastructures and political imaginations of Hill Country Tamils (Figure 1). It was unsurprising, then, to hear the crowd’s deafening cheers upon hearing Modi utter Thondaman’s name before he could even finish his sentence. The premier’s sonic rendering of their paternalistic past had touched their impulse for recognition within but also beyond majoritarian Sri Lanka.

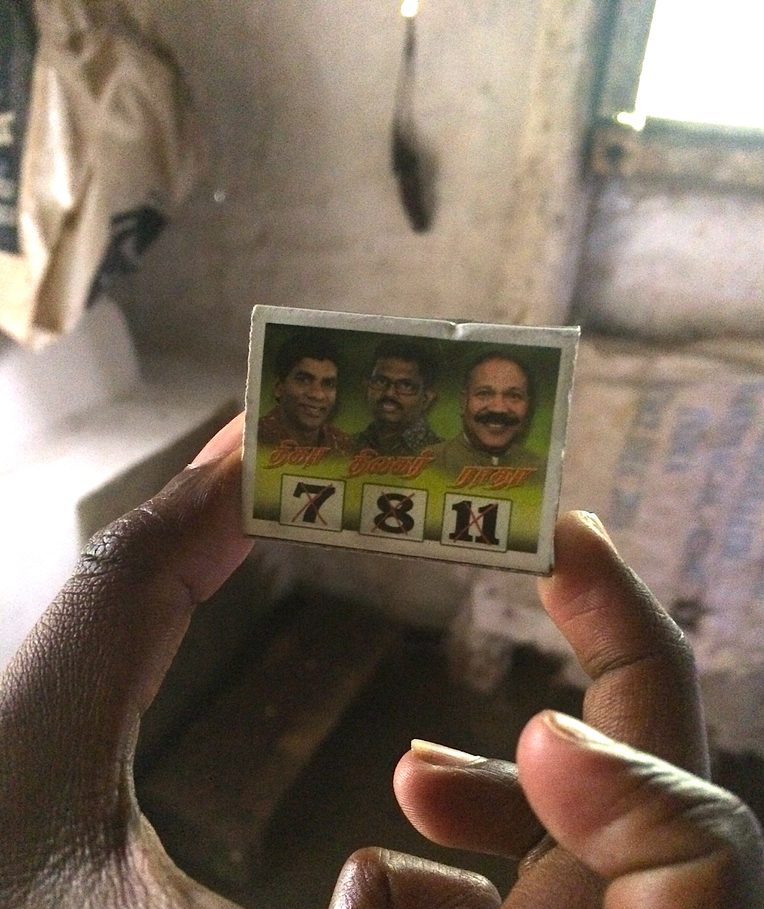

Hill Country Tamil politicians from Sri Lanka’s Tamil Progressive Alliance (TPA) sat on stage behind Modi. In 2015, I had followed their formation in opposition to the majority-aligned CWC closely, and in August that year, photographed one of their campaign matchbooks (Figure 2). In 2010, Palani Digambaram (candidate 7 in Figure 2) ran his first campaign as a “boy from the lines,”2—a decisive break from Thondaman’s wealthy, kankāni-turned estate owner heritage.3 In 2015, he campaigned in the lines by telling workers to raise their children to do anything other than plantation labor and had given a friend of mine this matchbook. The line of faces on the cardboard seemed to say, “If you trust this line, this place—this time—will be different.” I wondered then: would these faces be any different from those fading above orange and green bridges?4

Two years later, witnessing the lines of faces cheering Modi calls for a reimagining of Sri Lanka’s plantation paternalisms and how they animate Indo-Lankan diplomacies and ordinary desires for justice on the plantations. Plantation paternalisms nest into mostly male, densely packed Hill Country Tamil crowds, whose diasporic yearnings welcome an Indian state that once rejected their stateless kin. Live tweets and photo-ops activate their alluring “synchronicity of language and sight” (Carby 2019, 207) and render invisible the plantation’s “haptic temporalities” (Campt 2017, 72) of enduring exploitation and dispossession. These paternalisms sweeten the tea of Chai pe Charcha. No longer sold from Indian carts, these elixirs are sold as gifted houses on plantation markets. They hum the Tamil verse “Yaathum Ūrae” from the Sangam poetry anthology, Purunānūru. The refrain was once invoked by Periyar, a leader in the Self-Respect Movement during the same years that S. Thondaman assumed CWC leadership.

Will Modi’s offshore poetry blow out or reignite Periyar’s fires so inimical to the Brahmanical Hindutva agenda? Not knowing points to a twofold “hegemony without domination” (Hansen 2017) where Sri Lanka and India choreograph unregulated flexes of state power in minority Tamils’ imaginations. The ordinary desires of Hill Country Tamil civilians and workers also demand witnessing beyond the imperial confines of history in search of “potential history”: to find the less spectacular, everyday demands for dignity that fall into the ground-breaking cracks and move them into the “here and now” (Azoulay 2019, 287).

Cracks now form in the ground Modi broke earlier that day in May 2017. Before his address, Modi cut a ribbon at Dickoya Base Hospital, a site I have visited often during fieldwork. The date “12 May 2017” was inscribed on trilingual marble plaques, but I knew the hospital had been open since July 2015.5

In April 2008, a year before the war ended, Sri Lanka and India signed a Memorandum of Understanding (MoU) for the Indian Government to gift roughly ten million USD to renovate the hospital. But when the war ended in May 2009, those funds were transferred to war-zone reconstruction in the north and east. In June 2015, ahead of the parliamentary elections, Hill Country Tamils protested at the hospital, demanding it reopen. One demonstrator’s sign read in Tamil, “Don’t let the patients wander!” In July, it partially reopened to placate voters, and later that summer, I attended three funerals in one month. All three individuals had died within the hospital’s walls. The next month, a ribbon-cutting ceremony opened the renovated wing.

Plantation paternalisms are cultivating a speculative alchemy of postwar Indo-Lankan relations and an alternative politics of labor, recognition, and capital. Their concrete fills foundations on monocultured grounds. They engrave polished marble with men’s names whose faces no longer need matchbooks. They render Hill Country Tamil workers “children of Tamil Thai”on Lankan soil.6 One day, those “children” applaud for paternalistic pasts before sentences end, but the next day, they strike and demand their rights as a dispossessed, forgotten minority. Sewn into bilateral agreements, these paternalisms cut ribbons with sharp scissors in one town. Then, they go to a different town. Someone’s hometown. Soon, every town. Their sensorium steeps in the plantation’s soil as workers stand and refuse a future of wandering to die. For they have yet to taste justice on the hills they work to live.

1. During Modi’s first visit to Sri Lanka as prime minister (March 2015), the specter of the war remained. He did not visit the Hill Country but instead places significance to Buddhists and Hindus and Northern Province’s war zones, including a ceremony for Indian Peacekeeping Forces (IPKF).

2. Lines or “line rooms” are barracks, residential quarters for workers, dating from colonial plantation system.

3. Kankāni is the Tamil term for a plantation overseer. This term formerly referred to worker recruiters from South India. Thondaman’s father, a worker-turned kankāni, later purchased a tea estate, amassing great industrial wealth.

4. The CWC emerged from Ceylon Indian Congress (CIC) in 1939. The union uses the Indian flag’s orange and green colors often in their official materials. In May 2020, the flag adorned Arumugam Thondaman’s coffin on the same grounds where Modi gave the 2017 address.

5. Sri Lanka’s official languages are Sinhala, Tamil, and English.

6. Tamil Thai (tamizhttāy) or “Mother Tamil” is the historic-nationalist practice of deifying the Tamil language.

This essay has been corrected so as not to unintentionally imply that Periyar is Dalit.

Azoulay, Ariella Aïsha. 2019. Potential History: Unlearning Imperialism. London: Verso.

Campt, Tina M. 2017. Listening to Images. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Carby, Hazel V. 2019. Imperial Intimacies: A Tale of Two Islands. London: Verso.

Hansen, Thomas Blom. 2017. “On Law, Violence, and Jouissance in India.” Member Voices, Fieldsights, November 1.