Substitution: Introduction

From the Series: Substitution

From the Series: Substitution

Substituting one thing for another–things, people, habits–happens all the time. Substitution is so mundane that it can easily be taken for granted as a natural or insignificant process. Yet attention to substitution, including when and how it takes place, helps reveal a wide array of social, technical, and political dynamics. Substitutes hold sameness and difference in productive tension: they are imagined both as simple replacements, as well as innovations that enable function in excess of original form. More plentiful, more productive, more sustainable, more artificial, more natural, more homogenous–substitutions seek to be the same but also more desirable than what they replace. In this interplay of difference and similarity, substitution as an empirical phenomenon condenses social processes of change and/as continuity, rarely neutral even as it appears merely technical.

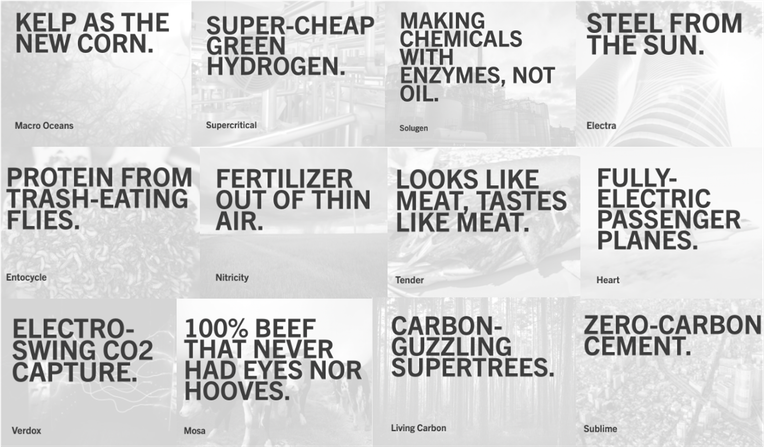

This series contributes to the growing scholarship that explores examples of substitution developed or emerging amid environmental threats (Badami 2021, Guthman and Biltekoff 2021, Ulrich 2023, Ehrenstein and Rudge 2024). These include renewable energy and materials to replace fossil fuels and petrochemicals, land-use changes that swap monoculture for ecosystems (or vice versa) and operate on the basis of interchangeable laborers, and carbon metrics and standards that come to stand in for pasts and futures alike. The essays collected here examine the ideological work that the concept and/or act of substitution performs as an ordering device and in its practical consequences. They consider how substitution is made common sense, what it achieves in success and failure, and what is obscured, masked, reframed, and displaced through or as substitution. They examine how substitutive futures and substitution as a concept are capable of environmental world-making in diverse ways. One common concern is how substitution is deployed to change existing power structures, or reinforce them. Thus in exploring substitution ethnographically, empirically, and analytically, the essays collectively advance substitution as a tool for tracing the often hidden paradoxes and ambivalences of social, political, and technical change (Figures 1 and 2).

For example, many of the essays demonstrate the myriad ways in which projects to implement change–whether in terms of climate change mitigation (see Abdelghafour, Boyer, Varkkey et al.) and/or longer but related trajectories of economic development (see Kotzen, León Araya, Jegathesan, Raj)–often end up obscuring the continuation of asymmetrical status quos in the name of meaningful difference. Substitution here is a forward-looking orientation shaped by the past and entrenched habits (see Pihl, Reche, Romero Dianderas, Ulrich). Yet other essays also explore the potential affordances of substitution in providing a gentler modality of transition more likely to be accepted compared to radical reform (see Knox et al.). And for some contributors, substitution creates simpler abstractions of the world in order to cautiously experiment with possible futures and their implications (see Cointe, Monteiro). These all constitute the varied political work that substitution achieves in its capacity to contain both sameness and difference at once. The series shows, ultimately, how thinking about substitution constitutes a method for tracing continuities amid seeming change, disruption amid seeming continuity, and possibility within constraint.

The series features essays from a group of authors diverse in terms of areas of research, institutional location, geographical origin, and career status. To us this was important given substitution’s pervasive but distinct operations across large swaths of social life, which is reflected in the heterogenous representations of substitution gathered here. Substitutive dynamics like those examined in this series also take shape within asymmetrical global economies–where change, continuity, similarity, and difference are variously displaced or externalized onto some for the benefit of others–requiring expansive analytical attention across geopolitical-economic contexts.

The series opens with six essays in which substitution is an emic category, one that guides announced, planned, projected, and resisted material changes in the service of supposedly more environmentally friendly futures. Dominic Boyer asks how we might imagine a successful successor to petrocapitalism, cautioning that electrification may not provide a real political alternative and looking instead to the emancipatory potential of electromagnetism. Béatrice Cointe considers multiple layers of substitution within the modeling of decarbonization efforts, yet also finds more potential in the exploration of alternative future horizons. Nassima Abdelghafour examines a kerosine-to-solar lamp exchange project in East Africa, where lamps and micro-entrepreneurial philanthropic models substitute for structural change. Bronwyn Kotzen highlights the politics of standardization amid an oil crisis in Nigeria, where modifying a material’s regulatory definition (here, cement) changes the market. Alongside energy, green products are another popular tech-based environmental trend hinging on substitution. Taking us to Brazil, Katie Ulrich shows that sugarcane-based bioplastics are startlingly similar to petroleum-based plastics (non-biodegradable, single-use), to the point that “the original haunts the copy.” In Denmark, Vibeke Pihl describes the efforts of the biotech sector and denim dying industry to replace harsh chemicals through a chemoenzymatic substitution that does not question the over-consumption of fast fashion.

In the next four essays, substitution is a macroeconomic process entangling commodity markets, trade, and geopolitics with environmental and social concerns like land use, labor, and human rights. Mythri Jegathesan follows the linguistic and conceptual slippage between tranches and trenches, as oil debts are paid off in tea equivalents through tea pickers’ labor in Sri Lanka’s tea trenches. Jayaseelan Raj considers racialized, substitutive labor regimes on colonial capitalist plantations in India that naturalize violence and oppression. Tracing longer histories in Costa Rica around import substitution, Andrés León Araya posits substitution as an index for passive revolution where everything changes only to remain the same. For Helena Varkkey, Rory Padfield, and Kate Manzo, peatlands in Malaysia that were once seen as wastelands are reconceived as treasure troves, yet through familiar colonial processes of valuation.

The last four essays experiment with substitution as an analytic device that opens even wider avenues for anthropological theorizing. Eduardo Romero Dianderas considers the role, and limitations, of mathematical abstraction when it comes to measuring and replacing the survey lines that conjure Indigenous territory in Peru. Examining scientific efforts to test the effect of higher CO2 levels in and on the Brazilian Amazon, Marko Monteiro considers how scientists generate speculative futures through substitutive experimentation. Clarissa Reche traces projects that mobilize synthetic biology to replace nature with biotechnologically produced realities, turning such substitutive framings on their head to consider synthetic biology’s eugenics-driven past. The final essay by Hannah Knox and colleagues brings us back to our own collective roles in the climate crisis and energy transition, offering substitution as indeed a method for destabilizing the status quo of individualized responsibility.

In all, the contributions posit substitution as a rich object of study as well as productive analytic for examining multidimensional entanglements of sameness and difference, continuity and change, and possibility and restraint. This is the first key point we hope readers will take away from this series. As an extension of this, we further suggest that substitutive dynamics may shape how we come to think about what change itself is. By interrogating the mechanism by which change is enacted and envisioned, the collection opens the grounds for asking how change might be reimagined–that is, asking what meaningful change really looks like, considering which axes or scales of similarity and difference could or should be targets of intervention, and giving attention to smaller or more subtle dynamics that might seed significant transformations.

Still, what substitution is, and its ramifications, are far from settled–nor is the potential of its analytic purchase in contemporary anthropological theorizing. Ecological crises have been centuries in the making (see the recent Theorizing the Contemporary series on the Plantationocene), and this interplay between inheritance, continuation, change, and transition is precisely what a focus on substitution helps surface. Yet going beyond environmental issues, anthropologists have previously studied substitution within contexts of sacrifice, exchange, care work, and generic drugs, theorizing processes of equivalency, qualification, and comparison (Evans-Pritchard 1956, Kockelman 2007, Mayblin 2013, Svendsen et al. 2018, Sanabria 2014, Hayden 2023). Our second key aim for this series is an invitation to likewise imagine other situations and analytical puzzles substitution may speak too. A broad range of social dynamics might be understood to pivot around similarity and difference. (See the range of topics and conceptual approaches during the two-part panel, “Different but Not Different: Ethnographies of Substitution,” during the 2019 AAA meeting.) If this series has demonstrated how substitutive futures and substitution as a concept are capable of environmental world-making in diverse ways, we conclude on our own curiosity about other worlds that anthropological theory and vocabularies around substitution could create.

We thank Nandita Badami for early conversations around substitution, and likewise the members of the 2019 AAA panel, “Different but Not Different: Ethnographies of Substitution,” organized by Katie Ulrich and Nandita Badami. We also thank the UCL Institute of Advanced Studies and UCL Anthropocene for facilitating and funding conversations and research that led to these ideas. Finally, we are appreciative to Lucy Sabin for letting us use her artwork as this series’ cover image.

Badami, Nandita. 2021. “Shadows for Sunlight: Epistemic Experiments with Solar Energy in India.” PhD dissertation, University of California, Irvine.

Ehrenstein, Véra, and Alice Rudge. 2024. “The Logic of Carbon Substitution: From Fossilised Life to ‘Cell Factories.’” Review of Agricultural, Food and Environmental Studies 105: 99–123.

Evans-Pritchard, E.E. 1956. Nuer Religion. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

Guthman, Julie, and Charlotte Biltekoff. 2021. “Magical Disruption? Alternative Protein and the Promise of De-materialization.” Environment and Planning E: Nature and Space 4, no. 4: 1583–1600.

Hayden, Cori. 2023. The Spectacular Generic: Pharmaceuticals and the Simipolitical in Mexico. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Kockelman, Paul. 2007. “Number, Unit, and Utility in a Mayan Community: The Relation between Use-Value, Labour-Power, and Personhood.” The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 13, no. 2: 401–17.

Mayblin, Maya. 2013. “The Way Blood Flows: The Sacrificial Value of Intravenous Drip Use in Northeast Brazil.” Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute 19, S1: S42–S56.

Sanabria, Emilia. 2014. “‘The Same Thing in a Different Box’: Similarity and Difference in Pharmaceutical Sex Hormone Consumption and Marketing.” Medical Anthropology Quarterly 28, no. 4: 537–555.

Svendsen, Mette, Laura E. Navne, Iben M. Gjødsbøl, and Mie S. Dam. 2018. “A Life Worth Living: Temporality, Care, and Personhood in the Danish Welfare State.” American Ethnologist 45, no. 1: 20–33.

Ulrich, Katie. 2023. “The Substitute and the Excuse: Growing Sustainability, Growing Sugarcane in São Paulo, Brazil.” Cultural Anthropology 38, no. 4: 439–66.